- Central Desi

- Posts

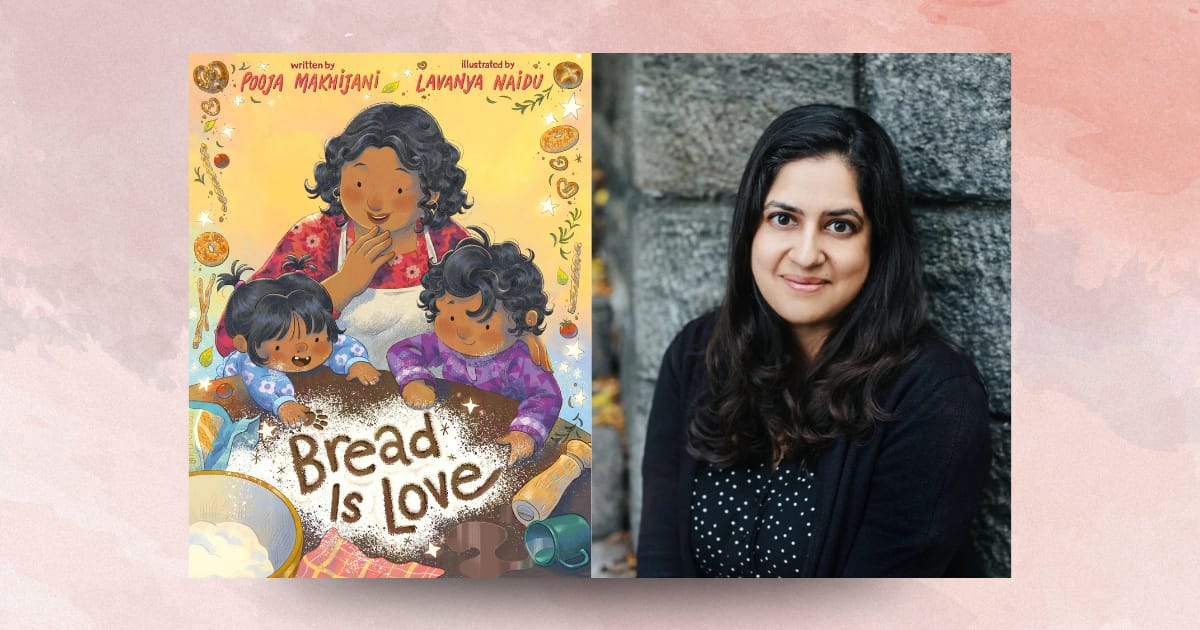

- Bread is Love: A conversation with Pooja Makhijani

Bread is Love: A conversation with Pooja Makhijani

The author discusses her upcoming book, diverse storytelling, and how acts of creation sustain us.

Pooja Makhijani has spent her career exploring the intersections of food, healing, and identity. While she has written for publications like The New York Times and Bon Appétit, she is best known for her children’s books. Makhijani doesn’t shy away from writing about taboo topics for younger audiences, including divorce, anxiety, and postpartum depression.

Her latest book, “Bread is Love,” publishing on Feb. 10, marks a pivotal moment in her journey as a creator. Born out of a period of personal transition and the chaos of the COVID-19 pandemic, the book is a gentle reminder of care work. With vibrant illustrations and a recipe at the end, it explores how acts of creation, such as baking, can help us navigate challenging emotions or turbulent times.

I sat down with Makhijani to discuss how “Bread is Love” fits into the growing landscape of diverse storytelling. She also spoke on Central Desi’s author panel in 2024, when she previewed the book by saying, “My upcoming book is about a ritual of breadmaking between a mother and a child. Are they making naan? No, they’re making sourdough…. It’s about how our culture means many things. There are pieces of me in my sourdough. Just because it’s a California-style sourdough doesn’t mean it’s not Desi.”

Once you can see yourself represented,

you realize you can be that person too.

Responses have been edited for brevity.

Your new book, “Bread Is Love,” is described as an ode to the rhythms of the kitchen. Why bread specifically? Were you always a baker?

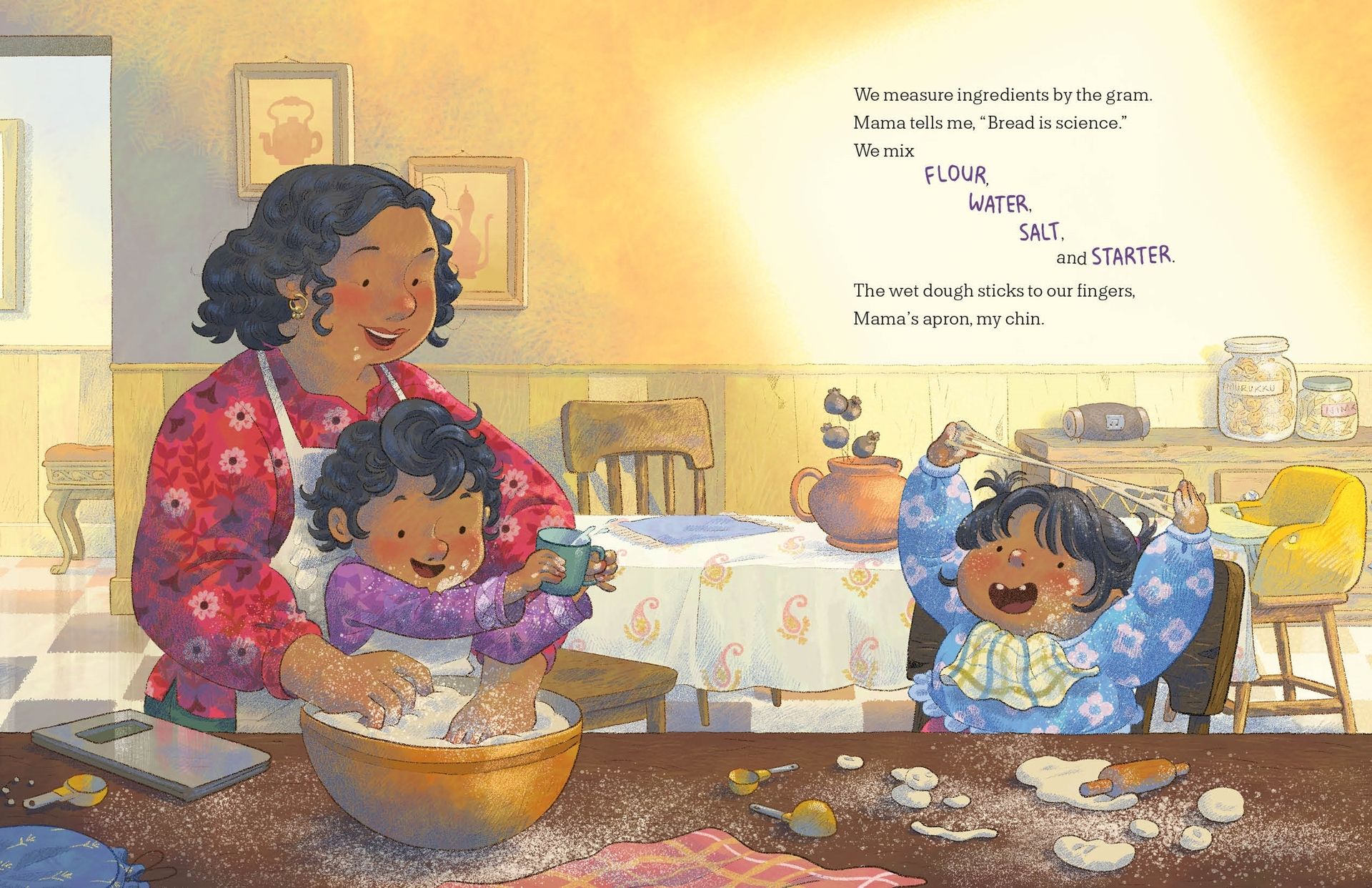

Pooja: I wasn’t a lifelong baker. In many Desi households, baking usually means brownie or cupcake mixes. For me, baking started about a decade ago during a major life transition. I had split from my husband and moved back in with my parents. In moments of anxiety and loss, I found myself scrolling on Instagram and decided to try baking. One night, when I couldn’t sleep, I baked raisin bread because my dad loves it.

It sparked something. Baking became a healthy way to harness my emotions. It eased my anxiety and enriched my relationship with my daughter as we began baking together. When you are rebuilding a family, feeding them becomes an act of care.

You’ve written for The New York Times and Bon Appétit. Did your food writing background influence this book?

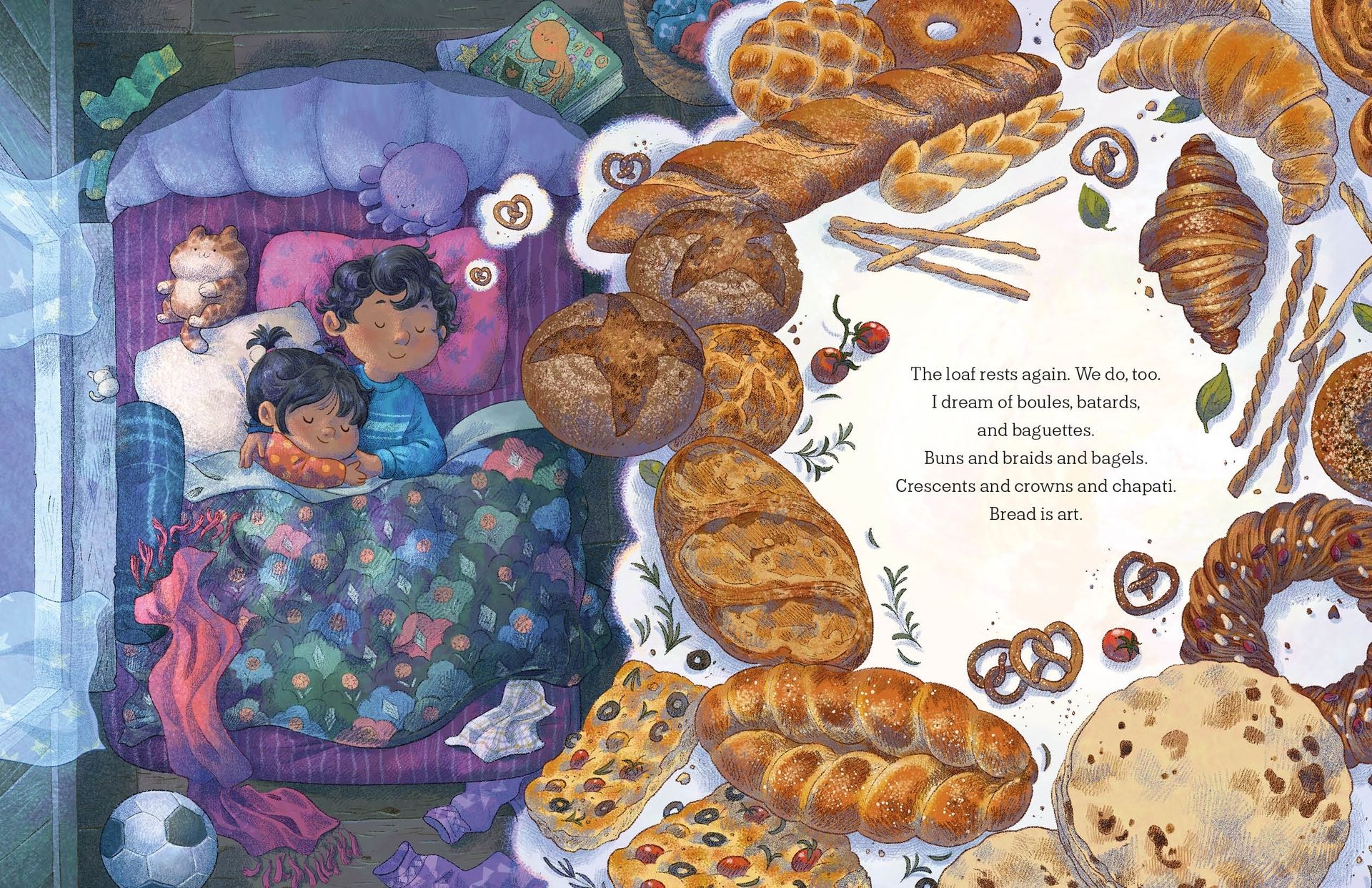

Pooja: Both require sensory awareness. You are trying to whet the reader’s appetite and evoke a specific feeling through words. Whether I’m writing for a home chef on Bon Appétit or a child, I want them to be enchanted by the process—the magic of making something and feeding those you love. That’s why I included a recipe at the end of this book, because I want people to experience the magic of making.

(Photo courtesy of Roaring Brook Press/Macmillan Children's Publishing Group)

Your first children’s book, “Mama’s Saris,” came out in 2007. What was the landscape like for South Asian authors back then compared to now?

Pooja: It was a completely different world. Back then, I could count South Asian children’s authors on one hand—people like Mitali Perkins or Uma Krishnaswami. There wasn’t a huge support network or the ecosystem we have now to amplify each other. During the pandemic, like so many others, I re-evaluated what I wanted to do. Seeing people pursue their passions was a catalyst that drew me back to writing for children.

Where do you see your story fitting into the current rise of diverse storytelling?

Pooja: There is a misconception that we are all fighting for the same slice of the pie, and perhaps we are in some ways, but I don’t see that in anyone. Everyone is excited about each other’s work. People are sharing things on Instagram and coming out to events, which creates an environment where we all feel supported. We’re seeing stories that span the diaspora across religion, class, and nationality. My June book release, for example, is about postpartum depression from a child’s perspective. I still think there’s a long way to go, but it’s exciting to see that our stories are no longer being treated as a monolith; they are unique because we come from so many places.

In all of your written work, the journalism and children’s books, you have this common thread of care work. How does that apply to writing for a younger audience?

Pooja: Care work is caring for each other and our community; it’s the throughline in everything I do. Those themes of healing, community, and family interest me, and I feel that they’re heightened now as things feel like they’re falling apart in the world. They are reminders to find your own people, chosen family, or whatever that looks like for you.

When writing for children, my guiding principle is to never underestimate them. Children have complex, nuanced emotional lives. I want to convey this to them and their caregivers. Children should be treated with deep humanity, love, and respect, and they can handle difficult topics.

I try to find books I love that do this and study what makes them resonate.

Let’s pull back the curtain on the production behind your book. What can you tell us about its journey to publication?

Pooja: I signed the deal in September 2022, and the book is coming out in February 2026, so it’s been a long journey! Picture books are incredibly collaborative. Unlike a novel, it’s like a play where you write the script, but others handle the staging. I had input on the art, but the editor and art director had final say. We found this wonderful illustrator, Lavanya Naidu, and there were multiple rounds of sketches before the illustrations were finalized. I saw the cover only days before the rest of the world did, and was overjoyed. The process to publish a picture book takes a long time because the production value is so high.

(Photo courtesy of Roaring Brook Press/Macmillan Children's Publishing Group)

What advice would you give to aspiring writers in the South Asian community?

Pooja: Tap into what your community looks like and build your ecosystem first. This could mean following writers on Instagram, reading books that resonate with you at the library, or shopping at local bookstores. Once you can see yourself represented, you realize you can be that person too.

If you want to write for children, there is a wonderful event in New York called Kweli Color of Children’s Literature Conference for BIPOC writers. From there, the next step is to write the best thing you can and share it. Publishing is a business; we all live under capitalism, right? We cannot control what happens once a story enters the market, but we can celebrate the joy we take in the act of creation.

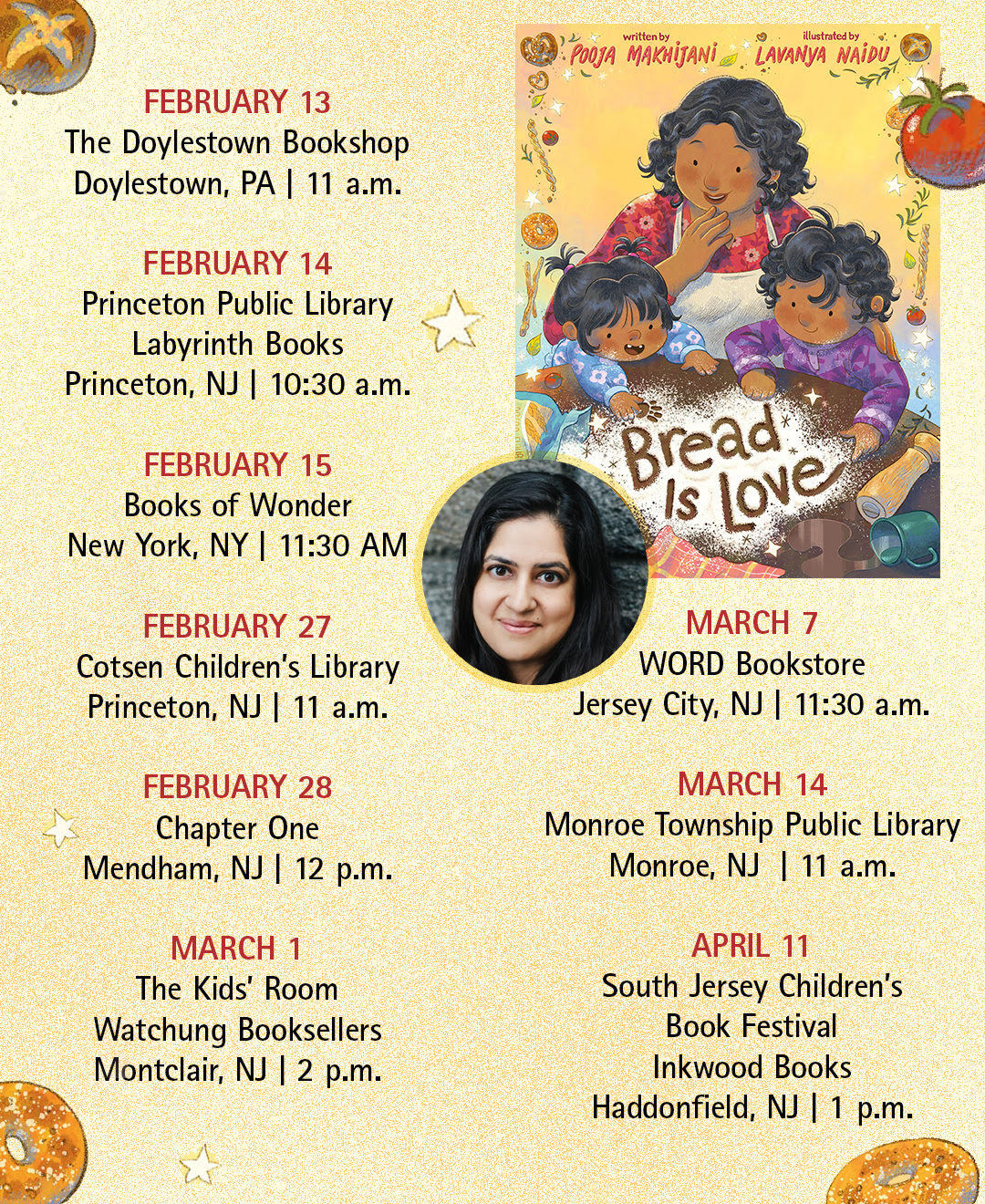

Meet Pooja and grab a copy of her book at one of these events.

(Image courtesy of Pooja Makhijani)

Ifrah Akhtar is the associate editor of Central Desi.

Reply to this email to chat with us, or join the conversation on Instagram.