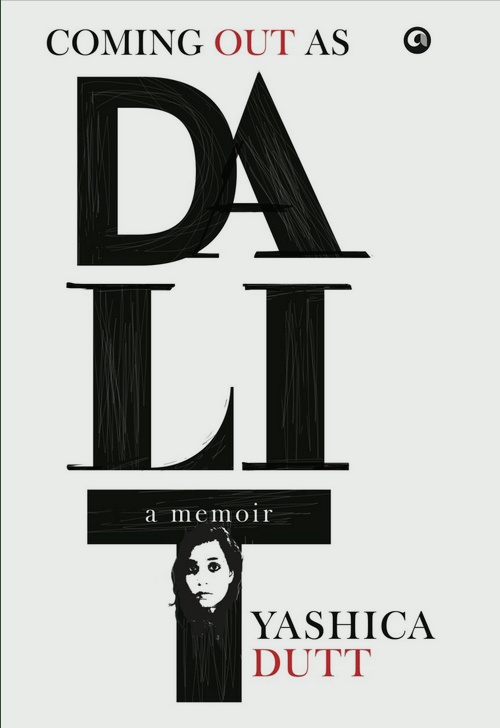

In Coming Out As Dalit: A Memoir of Surviving India’s Caste System, Yashica Dutt shares how her family hid their Dalit identity to strive for a better life in India. First published in India and now available in the U.S., the book is crucial reading for Americans seeking to better understand the politics of caste identity as it shapes South Asian communities in the States.

“Caste is not that visible here, but that doesn’t mean it goes away,” Dutt says in an interview with Central Desi’s Sofia Ahmed. “Back in India, at least 75 to 80% of the entire Indian population are lower caste people or Dalit. But in America, over 90% of people, according to some surveys, are dominant caste or from dominant caste backgrounds. Who’s getting to access this opportunity to be in the U.S? And who gets to define what Indian American culture looks like?”

You can read or listen to the full interview below. Share your thoughts with us by replying to this email, or join the conversation on Instagram.

An interview with Yashica Dutt, author of Coming Out As Dalit: A Memoir of Surviving India’s Caste System

Thank you so much for joining me today. I just wanted to start by asking if you could tell us a little bit about yourself?

Yeah, so glad to be here. My name is Yashica Dutt. I’m the author of Coming Out as Dalit, and I’m a journalist. I was born and raised in India. I came from one of the lowest castes in the caste system, a manual scavenging caste, which is a caste that is historically related with cleaning human excrement.

Just to give you some context, India’s caste system is ancient. It’s a system of hierarchy that segregates people into different castes, and it’s assigned by birth. So there is a huge population in South Asia of Dalit people in India, who hide their caste and I was one of them.

Yeah, thank you so much for sharing all that background. I was curious to learn more about why you wrote your memoir, and why you decided to “come out as Dalit,” as you phrase it?

I moved here in 2014, to New York, to come to Columbia Journalism School. And I started thinking about, you know, my caste more deeply. Like a lifetime of hiding this integral part of my identity, lying about it, living through fear, constant fear, that I’m going to be discovered, I’m going to be found out, what the consequences will be. Will my relationship completely fall apart? Will my workplace be the same?

You know, while I was in Columbia, another really important thing happened in the history of the Dalit movement, which was in 2016, a student named Rohit Vemula, who was at Hyderabad University, and who was actively calling out the university’s discrimination against him, was sidelined and he was tortured and was harassed to such an extent that he was forced to take his own life.

And in that process, he left behind this incredibly powerful letter. It conveys the anguish of being a Dalit person in India, the way he had been able to convey a lifetime of trauma, a lifetime of heartbreak, a lifetime of hopelessness. The reason I was able to acknowledge my caste identity in such a public and powerful way is because of Rohit Vemula.

Could you talk more about in what ways you experienced caste differently in the U.S. from your time in India?

In India, caste is very visible. It's always at the surface. It’s the conversation that people lead with when strangers meet each other: ‘What caste are you from?’

But in the U.S., caste is not that visible here, but that doesn’t mean it goes away. Back in India, at least 75% to 80% of the entire Indian population are lower caste people or Dalit. But in America, over 90% of people, according to some surveys, are dominant caste or from dominant caste backgrounds. Who’s getting to access this opportunity to be in the U.S? And who gets to define what Indian American culture looks like?

On this book tour that I just concluded, where I’ve been all over the country, and I’ve met so many Dalit students at each and every one of those colleges. And they’ve told me about the discrimination that they’ve faced on campus. So it’s not just discrimination within communities. It’s discrimination at the workplace, discrimination in neighborhoods, discrimination in educational institutions.

Would you be able to share a little bit more about the students you talked to, kind of anecdotally, like what forms that discrimination took?

Dalit students who I have spoken to, many of them have been hiding their castes here as well. That only proves that if caste did not exist, no one would need to hide who they are as part of Dalit identity.

At the University of Washington in Seattle, I spoke to a student who was actively harassed by dominant caste students and told to go back. Other people have talked about how they were told that, “Why have you come here in U.S. universities as well.” They often hear that, “Oh, you now got reservation or affirmative action in India, and you’re not happy with that. Now you’ve come here to harass us.” That’s how dominant caste students speak to Dalit students: “Now you’ve come here to take our share. Now you’ve come here to be in spaces that you don’t belong. Now you’ve come here to dirty this, muddy this pool.”

And if you look into the testimonies that people have given, many of them are students who talk about feeling actively unsafe on university spaces. First of all, feeling like they don’t have a right to be here. And secondly, feeling like their lives could be upended in any moment if their caste is revealed, or if the harassment reaches to a break.

Wow, yeah that is very sad to hear. I asked because at Central Desi, we wrote a story about why a bill to ban caste-based discrimination in New Jersey hasn’t been introduced yet. And opponents of the bill told us that it was unnecessary because caste-based discrimination is not a widespread issue, specifically in New Jersey, which has one of the largest South Asian populations in the U.S.

I saw you talked a little bit about the similar anti-caste bill in California that was vetoed. So I wanted to hear from you on why you think New Jersey hasn’t banned caste-based discrimination.

I was not involved in the process of passing of the bill in Jersey, so I cannot speak to the specifics of the situation. But from my experience of having seen how the opposition to the bill came about in Seattle, and then California, I’m not surprised that the bill wasn’t passed in New Jersey.

Your question is, despite it having a large Indian American population, why do you think the bill did not pass. I would say it’s because it has a large Indian American population. That is why the bill hasn’t passed. Because it’s the dominant-caste Indian Americans that are posing the greatest opposition to this bill. And that’s because, like I said, majority of the Indian American population comes from a dominant caste.

More and more Dalit people are now coming to the United States, whether as students or as professionals, and we don’t want to face the same harassment that we’re so used to facing in India. We cannot be a minority within a minority within a minority, who faces the kind of harassment that people outside South Asian communities don’t even understand. It is important for caste to be acknowledged as a widespread phenomenon within our communities, and it is important for Dalit Americans to get the protections that they deserve.

You raised a lot of great points, thank you for answering that. And then, my last question was about the current moment right now. I saw you’ve been pretty vocal online about campus protests calling for divestment from Israel, as you do this book tour and have visited different campuses and their connection to the Dalit liberation movement. Could you talk more about how the Dalit liberation struggle is connected to Palestinian liberation?

Yeah, absolutely, and I’m really glad you’ve brought that up. Especially over the last month and month and a half, I've been to many universities that were part of my book tour, where encampments were either going up or had just gone up the last day.

When I’m going from campus to campus to talk about why Dalit rights matter, it was very difficult to not see how the demands that we’re making within anti-caste communities are very similar to demands that are being made by the students and demands that are being made by pro-Palestinian supporters across the world.

I want to mention Dalits are a massive community. I don’t want to speak for everybody, I can only speak for myself. But I see Dalit liberation inherently tied to Palestinian liberation. Because we cannot ask for the world to witness our oppression while we close our eyes to a genocide or oppression of people happening elsewhere. We have to see our struggles as related to each other; we have to see the solidarity that can form with oppressed people around the world. So we have to fight for each other.

Sofia Ahmed was a 2023-24 reporting fellow at Central Desi.

Have some thoughts on this issue? Reply to this email to chat with us, or join the conversation on Instagram.