- Central Desi

- Posts

- Mother-son duo on Desi recipes, history, and collaboration

Mother-son duo on Desi recipes, history, and collaboration

“Heartland Masala” uses food to tell a story far greater than the dinner plate.

Last week, I had the honor of moderating a conversation with Jyoti and Auyon Mukharji, a mother-son duo who have authored the delightful new cookbook, “Heartland Masala.” We spoke at the Princeton Public Library, and thank all of you who came out to support the event.

This week’s issue summarizes the conversation I had with them.

“Heartland Masala” is the kind of cookbook that you could read cover to cover. It's not merely a list of recipes. It tells a story, not just of the Mukharji family and how they have assimilated in the United States, but also of South Asian history and how the cuisine reflects the region’s rich subcultures.

There are collections of essays in it that include slices of culinary history, from the foods of the Punjabi-Mexican community in Central California to how tandoori chicken came to be such a beloved dish in India. Peppered throughout this collection of 99 tried-and-tested recipes are insights into how modern South Asia came to be, evolving from a British colony to the nation-states we know today through Partition, an event that flung people of various regions and food cultures all over the subcontinent.

Responses have been edited for brevity.

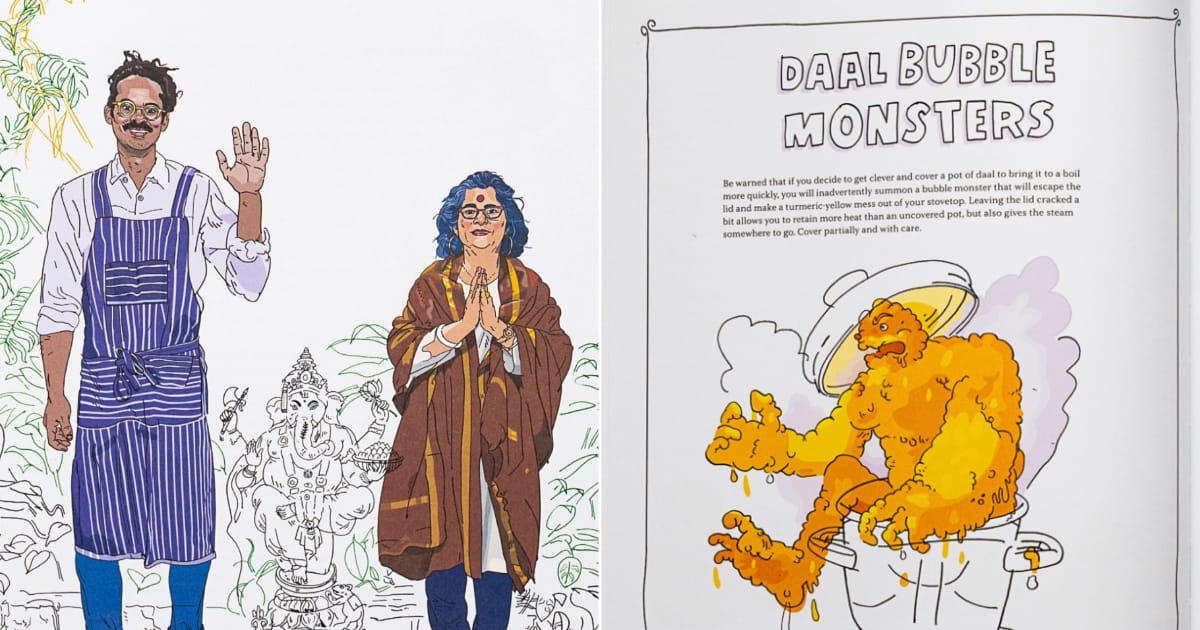

Illustrations by Olivier Kugler for “Heartland Masala.”

Jyoti, you had been teaching cooking classes for 14 years before publishing your cookbook. How did you become a cooking instructor to begin with, and when did the idea of the cookbook come to you?

Jyoti: I am originally a physician by trade. I studied and trained in India and the U.S. While in the U.S., I quit medicine to be a full-time mom to my eldest son, who has an offshoot of autism. In the early 2000s, I began volunteering on the Head Start board, a federally funded organization that provides support to underprivileged children, giving them a head start before they enter kindergarten in the public school system. For their annual fundraiser, they added a silent auction, and I decided to donate an Indian dinner for eight since cooking is a passion of mine. After doing this for four years, another board member suggested I offer a cooking class instead.

I taught my first class on Feb. 6, 2010. I remember the date, I remember the afternoon, I remember the people. It was as if I had achieved nirvana when I finished the class, because my passions for teaching and cooking came together. My husband commented on the glow on my face after that first class and said, “Why don't you do this as a hobby?” Well, folks, the rest is history.

Despite not advertising, having a website, or any social media presence, over the last 15 years, I’ve had 6,500 people in my kitchen, all through word of mouth.

All the profits from my cooking classes go to local charities I support in the city. The idea for the cookbook came when I was three to four years into teaching. My students asked me to write a cookbook with one requirement: Each recipe must have an accompanying photograph. I asked my son, Auyon, an excellent writer who had previously ghostwritten articles for me, to write the book with me.

Auyon, out of the three sons, how did you end up being the one who got roped into creating the cookbook with your mom?

Auyon: My older brother has a moderate learning disability, as my mother mentioned, which made writing challenging for him, and my younger brother is my mom’s secretary. She dictates her recipes to my younger brother, who types them for her. He is also an assistant professor at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, and thus has other responsibilities.

My mom asked me if I would work on the cookbook with her. My day job is as a musician in a band called Darlingside. At that moment, we were touring internationally. I was probably playing 120 shows a year, and the idea of writing a book with my mom in between made no sense.

But my mother is a very powerful woman, so I didn’t say no. I said yes, but before I do anything, you need to send me a list of all the recipes you want in this book. I knew that was going to be very difficult for her, because she has a lot of recipes she loves, and I thought she’d never actually get it to me. About a year and a half later, she sent me the recipes, and so we kept going.

There’s a Substack newsletter that you've launched, where we get a behind-the-scenes look at the cookbook tour. And one of the things you note is that South Asian mother-daughter cookbooks are trending, but “Heartland Masala” is slightly different. For one, you are Jyoti’s son. But you’re also learning from her; this isn’t the two of you putting your recipes together. Tell us what it’s been like to do this as a mother-son duo.

It ended up taking eight years to write. Three to four years in, she jokingly started threatening her own death. She was in good health, but was like, ‘I could die before this comes out.’

Auyon: My mom was psyched to get the cookbook out there. She thought we could get it out in a year and a half, spiral-bound with mediocre photos taken on an iPhone. I realized early on that, no matter what form it took, it would take a lot of time for me to be happy with it.

Writing yet another Indian cookbook of family recipes from an upper-middle-class Indian family was of zero interest, as there are many cookbooks in that genre. It’s a lovely genre, but I didn’t feel the need to add to it.

Through conversations with friends and reading cookbook reviews, I landed on the importance of history and context. I didn’t know much about it outside of being an avid Wikipedia reader, so I undertook a course of self-study. I didn’t really tell my mom what I was doing at the time, other than working on the book, and it ended up taking eight years to write.

Three to four years in, she jokingly started threatening her own death. She was in good health, but was like, “I could die before this comes out.”

Our collaboration was smooth when the hierarchy was clear: I wrote and she approved. On tour, I’m the management, she’s the talent. The real violence—the screaming, crying, and rude comments—happened during recipe testing. We are both passionate cooks, and as a Substack post details, we literally had to schedule time for our fights. For a period, we built in time for altercations three times a week, taking a break after a blowout fight and returning hours later to finish the recipes. This intense process is probably why there aren’t many mother-son cookbooks out there. Both mother and son were harmed in the making of this.

Let’s talk about what is in the book. Your family has a unique makeup within South Asia. Half your family is from Punjab and the other half is from Bengal. These are two distinct cultures. You’ve really pulled from the region and then your family’s own recipes, including sprinkling Doritos on rice and daal. How did you settle on the book’s 99 recipes?

Jyoti: I had presented about 103 or 105 recipes to Auyon. We whittled it down to 96 of mine and three of his.

Auyon: I have two cocktails and the last recipe in the book, a brittle. We followed a traditional Western cookbook standard in laying out the book.

When writing a cookbook, if you want someone to make the recipes the way you do, you must be precise and specific. But that is counter to the idea of encouraging experimentation and play. We offer a pathway for those who want to follow the recipe exactly, in addition to constant encouragement to fool around and experiment.

My favorite part of the book that facilitates this experimentation is the Spice Glossary. It includes the botanical and historical context for all spices, as well as how to use them outside of Indian cooking.

Our ultimate dream is for you to build a spice cabinet by making a few of our recipes and then start using those spices for things that have nothing to do with our book. That’s how you really build vocabulary and facility in the kitchen. For example, tamarind chutney is amazing with samosas, but it’s also incredible mixed into ice cream.

Auyon shares a map of South Asia designed for the cookbook.

(Photo courtesy of the Princeton Public Library)

Can you tell us more about the incredible map that shows the culinary history of South Asia but wasn’t included in the book?

Auyon: We worked with an excellent illustrator on the book, and the very first thing he created was this detailed, non-comprehensive map of South Asia. I was excited, but our publisher informed me we couldn’t include it. The map depicted all of India’s borders, including the highly disputed northern borders between India, China, and Pakistan (which our illustrator marked clearly). Our Chinese printer told us they were legally unable to print the map as-is and demanded we cut off the northern part of India. Rather than compromise the map’s integrity, we chose to remove it entirely from the book. We offer it as a free printable on our Substack and website for readers.

The book features unique elements like a humorous “American sauce” illustration, which critiques the generalized concept of “curry.” It’s also incredibly researched and you can find all the end notes online in a Google Sheet. How did those elements make their way into this project?

Auyon: We knew the backbone of the book was going to be my mom’s recipes filled in with the research I was doing. My younger brother, who is the assistant professor, is a historian who made me aware of how important footnotes are. I wanted the writing to feel light and accessible but also academically adjacent, so there is weight to what we were doing.

I had a vision for the illustrations and created mock-ups for our illustrator over the course of several months, which I thoroughly enjoyed. On the humorous side, there is something amusing about the fact that a mother and son created something together.

Jyoti, what year did you move to the United States from India? Tell us about the journey of how your cooking evolved.

Jyoti: When I first came here in 1978 with my one suitcase, I had Indian spices in it because I wasn’t sure what was available here. Cooking was a learning experience. I remember my first attempt at making my mother’s lentil recipe, toor daal, but I made it too tart by using excessive lemon juice as a substitute for unavailable raw mango. Over time, I became better at cooking and started substituting ingredients when certain Indian vegetables weren’t available, which led to recipes like my popular masala brussels sprouts.

Our family dinners became a compromise because my two older sons weren’t picky, but my youngest, Aroop, was a meat-and-potatoes kind of guy and fussed about having Indian food every night. My husband eventually intervened and we compromised: one day, Indian, one day Western.

What they didn’t realize until they were in high school was that my Western food always had an Indian twist, like pork chops marinated with my spices, which they loved. The cycle was finally broken when Aroop, at his own insistence, became a vegetarian for one year for a family thread ceremony. After enjoying vegetarian feasts in India, he returned to his school’s lunches of PB&J, pasta, and meat-focused foods. So, he asked, “Ma, can we have Indian every day?” From that point on, I cooked Indian food daily, marking a beautiful and memorable journey in our family’s cuisine.

A sneak peek of recipes from the cookbook. Photography by Kevin J. Miyazaki.

What’s the first recipe that you hope people will try from the book?

Jyoti: Start with the easier recipes in the book, like corn chaat or masala brussels sprouts, to overcome any intimidation you feel about Indian cooking. It’s true that the first time takes longer, but practice makes perfect.

I want you to be creative and bold. To make the process easier, treat your kitchen like a chef: Lay out all your ingredients and spices on the countertop before you begin so you don’t fumble. Read the entire recipe beforehand to familiarize yourself with the language and steps. We hold your hand with visual and time cues, and every recipe has been tested five or six times by our team for clarity and difficulty.

You don’t have to follow the book exactly, and you can never go wrong when you use fresh ingredients. Please do not use pre-ground jarred garlic or ginger. Invest in a dedicated spice grinder; a coffee grinder works if you promise not to grind coffee in it! Freshly grinding small batches of spices like cumin and coriander elevates your food to an entirely different level of fragrance and quality. Please use fresh!

Ifrah Akhtar contributed to this article. She is the associate editor of Central Desi.

Ambreen Ali is the founding editor of Central Desi and a journalist with two decades of experience covering politics, tech, and business.

Upcoming events this week (Nov. 19 - Nov. 27)

November 19 - Community Calligraphy Workshop with Zahid Mayo

5:30 PM - 7:30 PM

Haraz Cafe Fishtown

23 W Girard Ave #202

Philadelphia, PA 19123

Artist Zahid Mayo will lead a free calligraphy workshop at Haraz’s Fishtown location. Please note, you must bring your own materials! RSVP here.

November 22 - Heart & Hand for the Handicapped (HHH) Dinner Gala

Starts at 5:30 PM

Royal Albert’s Palace

1050 King Georges Post Rd

Fords, NJ 08863

HHH works tirelessly to empower children with disabilities by funding education, therapy, medical care, and vocational training programs. Join us for a fun-filled evening of dinner, entertainment, and community spirit, all while making a lasting difference.

Reserve a seat or table here.

November 27 - Thanksgiving Dinner and Karaoke

6 PM

Gagan Palace Indian Restaurant

33 S White Horse Pike

Stratford, NJ 08084

Celebrate a Desi Thanksgiving with amazing food, including turkey, and singing. There are limited seats, and RSVP details can be found here.

Have an event you’d like us to share? Complete this form.

Have thoughts to share? Reply to this email to chat with us, or join the conversation on Instagram.