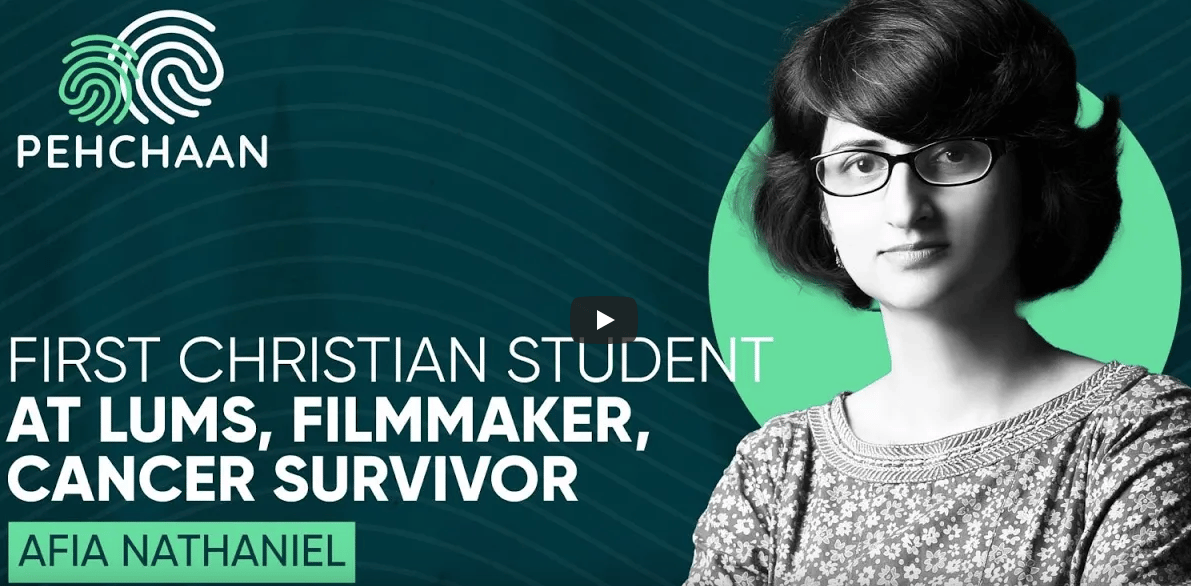

In 2014, a fictional thriller by a debut filmmaker, Afia Nathaniel, was all the sensation at international film festivals. “Dukhtar” is the story of a mother and her daughter on the run escaping a marriage arranged for the 10-year-old girl.

In Pakistan, where the film takes place, it broke genres by centering women in a fictional thriller and drew a new demographic to cinema houses: Mothers and grandmothers were bringing their families to come see the film that would become Pakistan’s official entry in the Foreign Language category of the Oscars that year.

At the time, Afia was living in New Jersey navigating other challenges. With a foreign language debut, she was struggling to break into the mainstream film industry in the United States. And, she had a complicated relationship with Pakistan, where she hailed from a community that has been marginalized. Being Christian was something she downplayed in Lahore, but that eventually became a point of pride in her multi-layered identity.

Fast forward a decade, and Afia has had a brush with cancer that made her, in her words, fearless. Based in New Jersey, she is boldly pursuing projects that are challenging the ways we think about South Asian identity and so much more.

The following excerpts come from the Pechchaan episode above. I’m co-hosting the podcast this season, and this is one of my favorite episodes because Afia was so open and vulnerable. Here’s some of what we discussed:

Growing up in Lahore:

I grew up as one of three girls, and I was raised by my grandmother, my nani, my nani’s sister and my parnani, my great grandmother, while my dad and mom were parked at some Air Force base. That was because they didn’t want our education to suffer, because in the Air Force, you get bolted around every two or three years.

It was a very unusual kind of upbringing in a very patriarchal setup. We were surrounded by Muslim families. We were the one Christian family and only women in the house, so we grew up trying to be invisible in some ways. Do not call attention on yourself, as women and as minorities also. It was a very sheltered upbringing. You couldn’t even step out of the house.

Being the first Christian to attend the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS):

I had never really thought about myself as a minority, because I had always learned to kind of not wear my identity on my sleeve…. The very first day at LUMS, we walk into this beautiful, massive new building, and they welcome us. There's a cake cutting ceremony, and then we walk out. As I'm walking around this gorgeous new campus, I bump into a cleaning guy who works at LUMS. He looks at me and he smiles, and he stops me, and he said to me, “Beta hum bahot khush hain ke aap yahan aayi hain LUMS mein. Humari poori community bahot khush hai.” Let me translate that. So this is a Christian sweeper at LUMS who stops me and congratulates me and tells me that we, the Christian community at LUMS, are so proud that you have come in as the first Christian student.

That night, I went home and I cried. I didn't realize. Because, you know, our community is called “chuhra” in Pakistan, we are referred to in a very derogatory way, which means the sweepers. At the time of Partition, you know, a lot of the the non Muslims who could flee, fled, but those who stayed were from very humble backgrounds.

A lot of the Hindus and the Christians who stayed back come from very, very marginalized and backward segments of the society. There's no upward mobility in Pakistan, so when I was at LUMS that day, I finally realized I represent my community, which is called the sweeper community, and today I have stepped into the that the highest echelon of education. I represent them, and to me that felt like an extraordinary privilege.

The challenges of being a Pakistani American female filmmaker:

In the US, filmmakers like myself get boxed into this little niche called “foreign language filmmaker,” where you're considered the other. Because your first film is not English language or in any colonial language, you're given this little sandbox to remain in.

It's not glamorous, I'll tell you that. So despite all the accolades, the critical acclaim of “Dukhtar” and everything, by the end of it, I was exhausted. I was exhausted trying to find work, trying to put food on the table for my family, and it wasn't happening. So I actually, in some ways, left the industry after the success of “Dukhtar,” because the reality was very harsh back then.

A cancer diagnosis and how it reshaped her career:

Last year I got some bad news, which was that I was diagnosed with breast cancer. It was an early stage thankfully, and I went through a whole process of healing. I'm still going through that process of healing. But what that has done to me is it was sort of a pause button in life.

It forced me to reflect in a very deep way, like, what is it that I want to do? What is it I want to say anymore? I I found myself going back to this thing that I love, which is telling stories. And so I said, Okay, I'm going to leave teaching. I have given many years of myself to others. I will now find a way to come back to this thing that I love and do it in a way where, because I know there's an urgency inside me now and there's a kind of fearlessness I did not have before.

This disease has taught me to not be afraid and to really take on the challenge graciously, fearlessly and with urgency.

Raising her daughter in New Jersey:

We have the privilege of being in a fantastic public school that really values diversity. For us, it was important as parents to find out, where should we settle or put down our roots, where should we call home, so that our child would grow up in a way where they feel they belong right there. And so growing up in this extremely diverse community here in New Jersey and going to a public school that values all of that has been a wonderful experience, and it has made my parenting job easier.

I feel our children's generation has a better chance of wrangling with [identity] on their own, because there's so much around them that does celebrate who they are now, versus the [previous] generation who grew up here. Their issues or their challenges were very, very different than the one that's growing up now. This new generation, they are growing up so comfortable in their skin that I feel like they are the ones who can change this world for the better.

Her current project and how it’s bringing together elements of her identity:

I have several other films and projects that I'm working on, and each of those projects gives me an opportunity to tap a part of me that may have been buried in some capacity. A lot of introspection goes on. As an artist, you're always thinking, ‘What is it about this material or this story or this character?’ You invest some part of you in that story or that character. I'm doing that in a way where I pay homage to the multi layers of religion and so on.

I'm currently working on a story that has to do with Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and Christians. And I find that I can easily tap into all of my experiences growing up and having an Indian husband who's from a Hindu family. And also I come from this, this very interesting [family] background where I have Christian, Muslim and Hindu spread out from all over India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and elsewhere, and Gujju and Pathaan and this and that. All of these identities have now become ready for exploration, and it's really fun diving into that and discovering a hidden layer of your own self.

Have some thoughts on this issue? Reply to this email to chat with us, or join the conversation on Instagram.